Current Status of Migration in Libya : Modus Operandi and New Trends

Éric DENÉCÉ

Migration to Libya is not a new phenomenon. Since the 1950s the country has held an important position as a destination for refugees and migrants coming from North, West and Central Africa, the Middle East and Asia, to work.

Since the end of Kadhafi’s regime in 2011, migrants departures from the Libyan coast towards Europe have broadly increased. Taking advantage of Libyan state failure, criminal transnational networks have flourished inside Libya. These networks involve a large range of actors, intermediaries and partners and are supported by some tribal militias and some members of Libyan security forces[1].

From 2014, the worsening of the Libyan conflict led to a significant increase in the number of migrants transiting through Libya, with some organized criminal groups taking advantage of the lack of border controls[2]. Weak governance and conflict transformed Libya into a major staging area for the transit of non- Libyan migrants seeking to reach Europe.

From early 2017 onwards reactionary migration measures were implemented in Libya and its southern neighbours to stem the flow of refugee and migrant sea arrivals to Italian shores. In 2018 refugee and migrant sea arrivals from Libya to Italy drastically decreased, with only 15,342 refugees and migrants reaching Italy irregularly via boat from Libya, a seven-fold decrease compared to the previous year[3]. However, the arrival of migrants has not been interrupted and has continued for the past two years at a similar pace.

While the overall number of refugee and migrant arrivals at Italy’s shores has drastically decreased since 2018, refugees and migrants still arrive in Libya.

-

Origin of refugees and migrants

According to the International Organization for Migration (IOM) UNHCR, there are 600,362 refugees and migrants in Libya[4]. The majority of them (66%) are from neighbouring countries : Niger (21%), Egypt (16%), Chad (16%) and Sudan (13%). This illustrates the importance of factors such as geographical proximity and diasporic ties in shaping migration dynamics to Libya[5].

Refugees and migrants from West and Central Africa (Niger, Chad, Mali) have traditionally come to Libya to work, with the view to support their families back home. But from 2018 their proportion among overall sea arrivals slightly decreased, as the economic crisis has made earning and saving money more difficult and rendered them more vulnerable to labour exploitation and robbery[6].

Refugees and migrants from East Africa (Sudan, Eritrea and Somalia) mostly seek only to transit via Libya on their way to Europe. Traveling in closed smuggling networks, with the journey usually organized already in the country of origin, their journeys to Europe have become longer and more dangerous over the course 2018. End 2018 East African respondents were found to have spent an average of 1 to 2 years in Libya, waiting to transit to Italy[7].

Refugees and migrants from the MENA region tend to be well integrated into Libyan society. They also tend to have been in the country for longer, often living there with their families. Asian refugees and migrants (mainly Bangladeshis and Pakistanis) also generally come to Libya to work. No major changes seem to have occurred in the situation for these two population groups over the course of 2018[8].

-

Routes to Libya

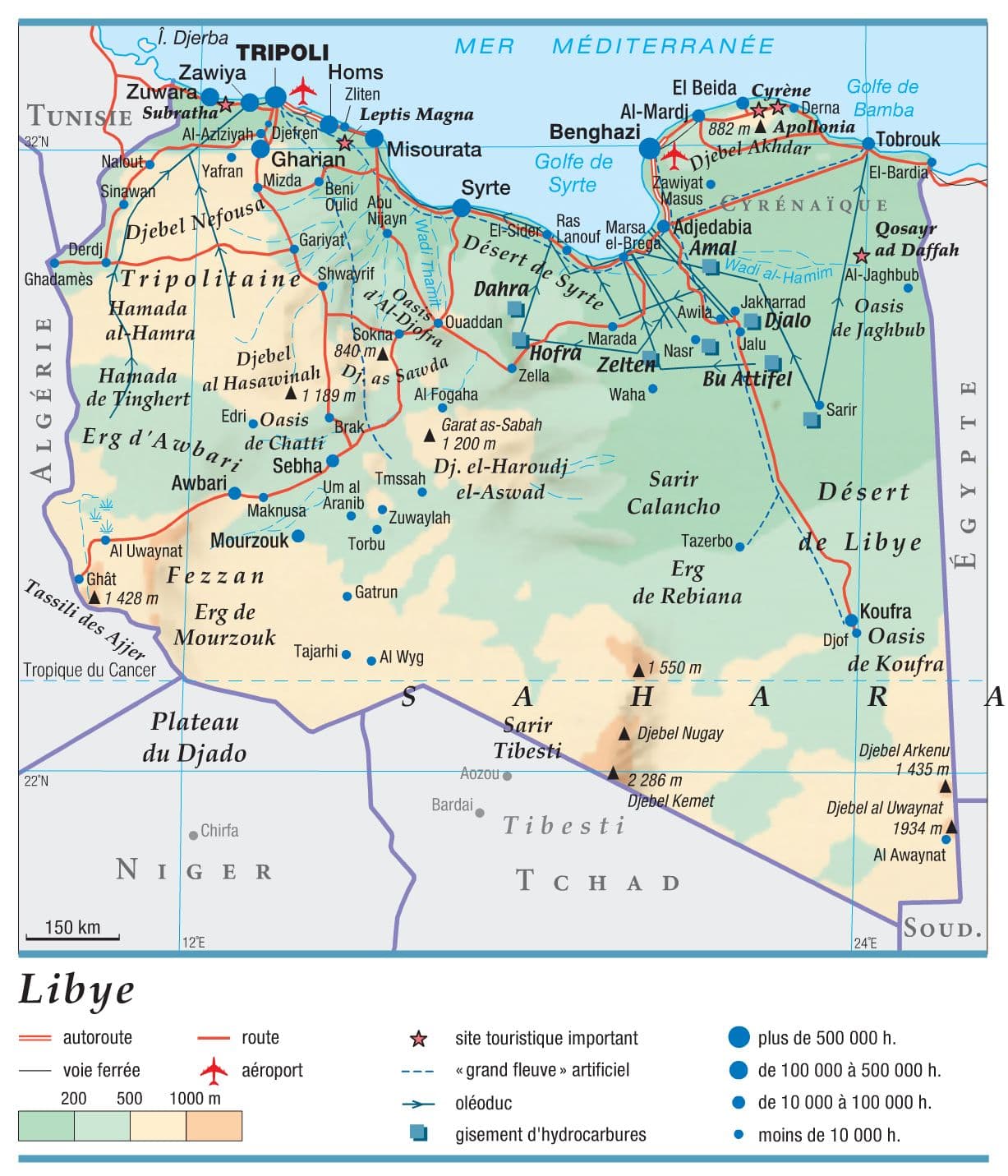

Routes and transit areas. Roads and transit zones in Libya are changing rapidly due to the extremely volatile security situation.

– North-Eastern Libya routes. Since 2015, the north-east of the country has been largely avoided by smuggling networks due to recurrent conflicts. A change of direction has emerged in recent years, due to protracted conflicts in Benghazi, Dernah, and Sirte : smugglers now avoid transiting these regions, preferring to pass through Gatrun, Sebha or Bani Walid[9].

– Southern Libya routes. The vast majority of migrants from East Africa enter Libya via Sudan and cross the border south of Sebha and Koufra. Travelers make fewer stops than in the past and are less inclined to stay for long periods because of the many conflicts that have affected this region in recent years[10].

Modes of travel. The smugglers active in Libya recruit many of their clients in schools, on the internet and by word of mouth. In the early 2010’s, some smugglers opened social networks to advertise their services[11]. Two modes of travel are used by migrants wishing to reach Libya and then Europe.

– “Organized » trips. This type of journey is mainly chosen by migrants from the Horn of Africa. The entire journey (from the country of origin to the country of destination) is supported by a transnational and structured network. People generally transit through Libya as quickly as possible and do not stop permanently in Libyan cities, where they stay in private dwellings on the outskirts of the cities. On average, the journey takes two to three weeks from the country of origin to the Libyan coast. In general, migrants pay for the whole trip at once. Migrants change hands several times during their journey to Europe, and do not deal directly with the intermediaries who accommodate them on the way. They are considered to be under the protection of their smuggler, who will theoretically be responsible for their safety until their final point of arrival[12].

– “Step by step » trips. Fragmented into several stages, these trips are organized by the migrants themselves, who use different smugglers at each stage of their journey. Travelers take breaks between each stage to work or receive money from their relatives to finance the next stage. The entire journey may last several months. This type of journey is undertaken mainly by people from West or Central Africa[13].

-

Migrant assembly areas and Maritime routes

The situation of refugees and migrants in Libya remains inherently complex. Due to their irregular situation in the country, they all tend to be hidden[14]. Nearly half of migrants (49%) identified in Libya in May and June 2020 were in the West, while more than a quarter were in the East (28%) and 23% in the South. Tripoli remains the host of the majority of migrants (14%) [15].

Detention centers. There are currently more than 2,400 refugees and migrants held in detention centers in Libya[16]. Those overcrowded centers are theoretically run by the Directorate General for Combating Illegal Migration (DCIM). But in practice, most of them are run by armed groups. The situation is constantly evolving, so that new centers open, while others close, at any time.

Embarkation areas to Europe. Along the Libyan coastline, numerous « transit houses » surrounded by high fences are visible. Migrants stay there, for several days or weeks, until their smugglers decide that the conditions are right for the crossing[17].

– Transit areas in Northwest Libya. The embarkation points are almost all concentrated on the west coast of Libya (over a distance of 200 km between Misrata, 250 km from Tripoli, and Abi Qammash, about 20 km from the Tunisian border), as it is the closest point to the Italian island of Lampedusa. Migrant boats usually departing from beaches and spots located around Zuwara, Sabratha and Zawiya (west of Tripoli) and Tajura, Garabulli and Bani Walid (east of Tripoli). Departure zones form a continuum and some other minor spots are sometimes used by smugglers : Surman and Al-Mutrid (between Sabratha and Zawiya) are gaining importance[18].

– Transit areas in Central Libya. Sirte was once a gathering point for many migrants. When the city fell under the yoke of the Islamic State (ISIS) in February 2015, migrants were exposed to the risk of being abducted or killed by supporters of ISIS. Some were executed for propaganda purposes. So, smugglers and migrants preferred to avoid this town and favored Ajdabiya, in the East[19].

Central and Western Mediterranean sea routes. Over the course of 2018 a change in the predominant use of these routes has been recorded with a three-fold increase in the number of refugee and migrant sea arrivals to Spain compared to 2017. Some West African nationalities who in 2017 were among the primary arrivals in Italy, predominantly arrived in Spain in 2018[20]. In total, more than 11,000 migrants arrived by sea to Italy in 2019, with the vast majority having departed from western Libya. In comparison, in 2016, more than 181,000 migrants arrived by sea to Italy[21].

Eastern sea routes. Boats departing from eastern Libya are bound for Greece or Turkey. Both countries having turned back several boats, this sea route has been closed. However, secondary roads have locally reappeared during 2018, as there was a steady increase in migration routes from eastern and south-eastern Libya converging on Ajdabiya. This increase was mainly driven by a large group of East African asylum seekers, who had been stranded in Cairo and Alexandria, crossing the Egyptian border in the hope of reaching Europe from the Libyan coast. The flow has since diminished[22].

-

The smuggling networks

The smuggling industry in Libya today is composed of a multitude of actors who vary widely in size, degree of organization and experience. There are not only Libyans in the industry but also many foreign nationals, usually acting as migrant recruiters but sometimes also as high-level middlemen and coordinators[23]. Armed groups, criminal gangs, smugglers and traffickers cooperate or compete fiercely for migrants’ money in Libya, as do some members of Libyan state institutions and some local officials. The Libyan Coast Guard often acts in complicity with smuggling networks[24].

The major groups are undergoing a process of professionalization. This is illustrated by the division of tasks of their members, the variety of services they offer, and their linkages to other groups along the migrant route, from countries of origin to destination. International rescue missions moving closer to the Libyan coast since 2014 also allowed smugglers who dispatch migrant boats to scale down on equipment and services, the objective no longer being to reach European mainland but only international waters[25]. However, the withdrawal of European search and rescue (SAR) missions off the Libyan coast has had an impact on the behaviour of coastal smugglers, who have returned to pre-revolutionary methods[26].

Traffic and activity in smuggling hubs fluctuate based on the local political and security context. In all these coastal cities, the balance of power between tribes, militias, security forces and criminal groups is constantly shifting, with these actors allying or opposing each other, taking advantage of or limiting the passage of migrants. This explains the variation in the importance of coastal departure points according to the local security situation.

-

Recent developments

Impact of internal conflict. Since April 2019, conflict has been raging in Libya between two rival coalitions of thousands of fighters supported by foreign powers in violation of a UN arms embargo. Fighting in June 2020 displaced 28,000 people in the western and central regions, bringing the total number of displaced persons to more than 401,000[27].

This civil war is creating a chaotic situation. While this may have the effect of discouraging some migrants who want to go to Libya to work, on the contrary, it reinforces the opportunities for the development of networks of smugglers and traffickers that migrants use to get to Europe as it diverts the action of the security forces from the fight against trafficking networks.

Evolution of arrivals. The number of migrants identified to be present in Libya decreased by 4% between April and June 2020. This decline is the result of the increasing unemployment rate, the reduction in available labour opportunities for migrant workers, tightened security controls and the mobility restrictions due to the COVID-19 pandemic[28].

Points of Entry (PoE) in Libya remained closed for entry since spring 2020 due to mobility restriction measures imposed to curb the spread of COVID-19[29] (Debdeb and Essayen with Algeria and Libya, Emsaed with Egypt, Ras Ejdeer with Tunisia and Altoum with). Anyway, several land border crossings were periodically opened to let groups of migrants leave the country[30].

Evolution of departures; Departures from the Libyan coast continued the downward trend that began in July 2017. Western sanctions, imposed on Libyans involved in smuggling, have played a role in the behaviour of armed groups in Libya. The Libyan Coast Guard (LCG) did not play a major role in reducing departures, which is largely the result of events on land[31].

However, migrants continue to leave the Libyan coast in large numbers, due to a variety of factors, including the deterioration of security and living conditions in Libya and the increased activity of smuggling networks[32].

An increase in irregular transit migration across the Mediterranean Sea to Europe was observed in May and June 2020, with 3,485 arrivals from Libya and Tunisia reported in Italy, compared to 2,000 arrivals in the same period in 2019. Between January and June 2020, a total of 6,950 migrants are estimated to have arrived in Italy, which represents an increase of 150% compared to the number of arrivals reported for the same period in 2019 (2,779 people)[33].

In 2019, the (LCG) rescued/intercepted 9,035 refugees and migrants at sea[34]. As of 17 September, 8,074 refugees and migrants have been registered as rescued/intercepted at sea by the Libyan Coast Guard (LCG) and disembarked in Libya[35].

*

Since 2018, when there was a very significant reduction in the phenomenon, Libyan immigration trends have not seen major changes and remain broadly the same. The variations observed are mainly cyclical or regional.

There is a « seasonal » evolution of departure points, but no reduction in their number. Modus operandi, itineraries and transit zones of smuggling networks are variable and adaptable to evolutions in the security situation.

Variations in the number of migrant arrivals in Libya are linked, on the one hand, to the security and control measures taken by countries of origin, and on the other hand, to Libya’s economic difficulties, the local conflict development and the COVID-19 epidemic, which make the country somewhat less attractive.

Libya is expected to remain an attractive destination for labour migration in the region, particularly for those with a high risk appetite and given the lack of other attractive destinations in North Africa.

Transit migration from Libya to Europe is also expected to continue, particularly due to the steady flow of West African migrants fleeing insecurity and poverty in their countries of origin. They could lead to a change in the route of the Western Mediterranean, as they now try to reach Spain.

[1] OFPRA, Les réseaux de passeurs en Libye, 30 novembre 2018.

[2] Ibid.

[3] UNHCR, Mixed Migration Routes and Dynamics in Libya in 2018, June 2019.

[4] UNHCR, in its report UNHCR Libya Response in 2020, 18 september 2020, gives the figure of 928,989 migrants end refuges, but it includes Internal Displaced Persons.

[5] International Organization for Migration (IOM), Libya’s Migrant Report Round 31, May-June 2020. According this report, the number refugees and migrants in Libya is only 600,362.

[6] Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime (GIATOC) and Clingendael (Netherlands Institute of International Relations), The Human Conveyor Belt Broken – Assessing the collapse of the human smuggling industry in Libya and the central Sahel, March 2019.

[7] GIATOC and Clingendael, The Human Conveyor Belt Broken.

[8] UNHCR, Mixed Migration Routes and Dynamics in Libya in 2018.

[9] OFPRA, Les réseaux de passeurs en Libye.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] UNHCR, Mixed Migration Routes and Dynamics in Libya in 2018.

[15] IOM, Libya’s Migrant Report Round 31.

[16] UNHCR Libya Response in 2020, 11 september 2020.

[17] OFPRA, Les réseaux de passeurs en Libye.

[18] Altai Consulting, Leaving Libya. Rapid Assessment of Municipalities of Departures of Migrants in Libya, Report prepared by for the Embassy of the Netherlands to Libya, June 2017.

[19] OFPRA, Les réseaux de passeurs en Libye.

[20] UNHCR, Mixed Migration Routes and Dynamics in Libya in 2018.

[21] Christopher M. Blanchard, Libya: Conflict, Transition, and U.S. Policy, Congressional Research Service Report, RL33142, June 26, 2020.

[22] GIATOC and Clingendael, The Human Conveyor Belt Broken.

[23] Altai Consulting, Leaving Libya.

[24] OFPRA, Les réseaux de passeurs en Libye.

[25] Altai Consulting, Leaving Libya.

[26] GIATOC and Clingendael, The Human Conveyor Belt Broken.

[27] Christopher M. Blanchard, Libya: Conflict, Transition, and U.S. Policy.

[28] IOM, Libya’s Migrant Report Round 31.

[29] Covid-19 Mobility Tracking #3, Impact On Vulnerable Populations On The Move In Libya, 30 July 2020, United Nations Central Emergency Response Fund (CERF).

[30] IOM, Libya’s Migrant Report Round 31.

[31] GIATOC and Clingendael, The Human Conveyor Belt Broken.

[32] Ibid.

[33] IOM, Libya’s Migrant Report Round 31.

[34] UNHCR Update Libya, 3 January 2020.

[35] UNHCR Libya Response in 2020, 18 september 2020.